There is a kind of tea in China, which is almost unknown in the West today, in spite of the fact that it has a long history and is in demand in Asia. This is Hei Сha, 黑茶. “Hei сha” literally means “black tea”, but this “black” is quite different from the well-known one.

Hei cha is usually made from fully expanded, mature leaves with stems and cuttings, so during the preparation process, they do not lose integrity, despite a rather harsh handling. Slightly dried in the sun, the leaves are fried, twisted and placed in large piles which are sprinkled with water and left to develop taste for several days. This step is called Wo Dui (渥堆, wet stacking). Fermenting inside the tea pile the leaves become darker, change their flavour and acquire new properties. Particular qualities of the source material, the time of maturing in piles, and further manipulations vary between regions. But all kinds of Hei Cha have the maximum degree of fermentation (up to 100%), darkly coloured, dense, with the full-bodied flavour and a distinctive aroma with notes of earth, wine, and wood. The most famous today are Hei Cha from Anhui, 安化黑茶 (Hunan province), Liu Bao Cha 六堡茶 (Guangxi province), Lao Qing Cha 老青茶 (Hubei province) and Bian Cha, 四川边茶 (Sichuan province).

(photo: Anhua Heicha in tiles, rolls and loose sheets, prepared for shipment to Russia)

HEI CHA FROM HUNAN PROVINCE

Hei Cha in Hunan Province has been known since the 16th century, as mentioned in the "Records of the national economy of the Ming Dynasty" in 1585. Its main consumers were the Tibetans, the nomadic peoples of Central Asia and Southern Siberia, in fact, more than 2/3 of the tea was sent outside of China.

(photo: Anhua Heicha manufacture, XIX century)

But in the beginning of the twenty-first century, the tea from Hunan shone in a new light as a "classic of tea culture, the essence of tea history and the top class tea product". At the first festival of Hunan black tea in October 2009 held in Yiyang, this city received the official status of "birthplace of the Chinese black tea".

(photo: Yiyang area)

The leaves are harvested in late spring when the young shoots are fully developed. The collected leaves are uniformly moistened with water (in the proportion of 1:10) and fried in large pans at a temperature reaching 320⁰C in batches of 4-5 kg. Once the leaf loses its elasticity, gets covered with juice, darkens and changes the flavour, it is rolled up in preparation for the main stage – wet stacking. On a clean floor in a dark room, the tea is placed in a small pile 1 meter high covered with a damp cloth.

After a few days, the pile is dismantled. The leaves, that had time to straighten up a bit, are rolled up again and then laid to ferment one more time. 15-20 days of fermentation under a constant control of temperature and humidity create a distinctive taste of Hunan Hei Cha.

(photo: Heicha manufacture)

Finally, the leaves which are now completely weakened and blackened are dried on a high heat. During the Ming dynasty, this had being done in a special oven called “Seven Stars” (the traditional image of the North Dipper constellation). Its design feature were seven holes around the perimeter of the air supply. The oven was fired with pine wood which gave a special smoky flavour to the tea. Nowadays tea leaves are dried on trays of large modern furnaces, but even they are heated over an open fire of pinewood or charcoal which is a distinctive feature of the technology. The tea leaf is very slowly impregnated with smoke on a gentle heat. Smoking (Hong Bei, 烘焙) takes from eight to thirty hours until the leaf, which is quite dark already, gets an oily gloss. After all these steps, we get the tea semifinished “mao cha”, which will then be kept for several years. It either can be left as loose leaf tea or pressed into the shape of bricks or rolls.

(photo: during the last 400 years the main occupation of the inhabitants of this small village is Heicha manufacture)

Loose leaf San Jian (三尖, Three Spikes).

Also known as Xian Jian (湘 尖, Hunan Spikes). The best tea is made in Gao Jia Xi (高家溪) and Ma Jia Xi (马家溪). San Jian (三尖, Three Spikes) have three grades. Tian Jian (天尖, Heavenly Spikes) is the top grade, premium black tea produced from the best source material. Gong Jian (贡尖, Gift Spikes) is the second grade, produced from the upper 3-4 leaves. Sheng Jian (生尖, Live Spike) is the third grade, produced from the mature leaves with stalks. All grades are inherent in rich aroma and saturated flavor with wine, tobacco, woody and earthy notes.

(photo: Heicha maocha)

Hua Juan (花卷, Decorative rolls).

First appeared in Yuzhou area of Anhua County at the beginning of the XIX century, when the volume of tea export has started to grow rapidly. Tea dealers from Shanxi and other provinces had built factories and sales offices on the banks of the river Zi. Here they were brought tea bought from the peasants in the villages for future packaging. For the convenience of transportation, at the factories the tea was rammed into bundles weighing approximately 100 liang (about 3.8 kg); this kind of tea has been called bai liang cha (百两茶, One hundred liang tea). Later the weight increased to a thousand liang (37,27 kg) and leading to Qian Liang Cha (千两茶, One thousand liang tea). A tightly compacted cylinder was braided with palm leaves and bamboo bast, which left a distinctive impression on tea rolls, so these rolls also called Hua Juan (花卷, Patterned rolls). The length of one thousand liang cylinder was 5 chi (1.666 meters), the circumference was 1.7 chi (56 cm). This tea has got a pretentious name “the Tea Master of the Universe”. Dealers from Shanxi were making tea in the counties Qi and Yu Ci, so their teas have been called “Qi Yu Ci rolls”. Jianzhou teas were made by dealers from Jianzhou and weighed 1100 liang. These Hua Juan (花卷, Patterned rolls) braided with a bamboo mesh travelled far beyond the borders of China.

(photo: the famous wooden bridge at the Tea-horse's Road across the river Ma near the village of Sitancun, built in the 19th century)

Nowadays for the convenience of commerce, all rolls are sawn into cakes which are sold in boxes. Compositions made of the original Qian Liang Cha, the “One thousand liang logs”, became a mandatory decorative element of tea shops interior.

(photo: famous One thousand liang logs)

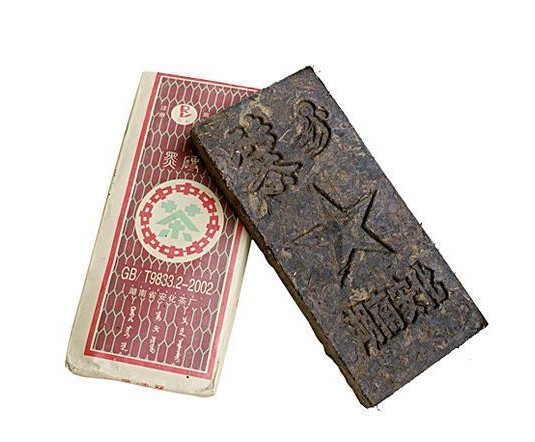

Anhua Hei Zhuan (安化黑砖, Black brick tea from Anhua).

Appeared in the 40-s of the XX-th century, thanks to the efforts of Mr. Peng Xianjie, deputy head of the tea department of Hunan Province. By his initiative, the first black bricks were created in Anhua’s Jiang Nan Pin (these days Jiangnan) using the method developed in Yang Lou Dong (Hubei province), where in the second half of the XIX-th century Russian merchants established the first trade offices and opened factories. In 1939 Mr. Peng Xianjie ordered six manual screw presses from Hunan area Xiangtan, and in March 1940 the Hunan pressed black tea production line was officially opened. As soon as this happened, with the assistance of the Chinese tea company the first batches of black tea bricks went from Anhua to the Soviet Union.

Currently, two types of black bricks are produced – Hei Zhuan Cha (黑 砖茶, Black bricks) and Hua Zhuan Cha (花砖茶, Decorative bricks) with patterned embossing. There are also green bricks Qing Zhuan Cha (青砖茶) which are made of pressed green leaf that has not undergone wet stacking.

(photo: sawn Qianliang log)

Fu Zhuang Cha (茯砖茶, Longevity bricks).

The name of Fu Zhuang Cha (茯砖茶, Longevity bricks) is a wordplay. Originally the name was Fu Zhuang Cha (伏砖茶, Brick tea made in the heat). At the same time, it refers to the healthy properties of the Longevity Mushroom, Ful Ling (茯苓, Poria cocos). Furthermore "Fu Cha" sounds like "The Happiness Tea". Until the middle of the Twentieth Century it was made entirely by hand, but in the 50-s the specialists from Shaanxi Jing Yang, led by Professor of Biology Zhao at Wuhan University developed a mechanized production. In 1953 the technology was perfected and from that moment the modern history of the Fu Zhuang tea began.

A distinctive feature of Fu Zhuang Cha is the compulsory presence of fungal culture Jin Hua, or “golden flowers” (Eurotium Cristatum). It looks like yellow grains scattered on the surface of the tea leaves. And the larger the size of the gold pea flower, the better the tea. Thanks to them, Zhuang Fu Cha tea has a beneficial effect on health: improves digestion, lowers cholesterol, normalizes blood pressure, improves overall metabolism, and also has a pronounced antibacterial effect.

(photo: Fu Zhuang Cha)

The mineral elements in tea tree are concentrated mainly in the mature leaves, stems, and stalks. Since exactly this kind of a raw material used in the production of Hunan Hey Cha, the high content of the fluorine has a positive effect on bone strength and selenium stimulates the production of antibodies and immunoproteins, increases resistance to diseases. It is effective in preventing coronary heart disease, prevents the formation and development of cancer cells. In the famous “Ben Cao Gang Mu” (本草纲目, "Treatise of the officinal plants") the great medieval scientist of China Mr. Li Shi Zhen (李时珍) has said: "Tea in Anhua is made from Hunan large-leaf tea varieties, it has stems and it is rough. It needs to be either simmered or brewed with a boiling water in a teapot, only due to the high temperature its taste is appearing and colour becomes dense and black. In its bitter taste, there is sweetness hidden. This tea helps to digest food and is pleasing to stomach, it has a warm nature and dispels the cold."

(image: the ancient tea ceremony)

Modern research confirms that Chinese black tea is very good for health. It contains tea polyphenols – theaflavins and thearubigins, which not only give it a distinctive dark colour, but are also effective as antioxidants, have an antibacterial and antiviral effect, treat cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, reduce blood lipid levels and blood pressure, prevent bonding of blood cells and clot formation, inhibit the propagation of cancer cells and enhance the immune system, and are useful for regulation of fat metabolism and weight.

(image: the modern tea ceremony)

Common for all of Hunan Hey Cha is the distinctive orange-yellow colour of the infusion, dense and mature aroma with wine notes and a dense rich taste turning to sweetness.

In spring 2014 we filmed a detailed report on the production of black tea in Anhui, with some sketches from the places where tea is growing and a lot of the other interesting information.

HEI CHA FROM GUANGXI REGION

Liu Bao Cha (六堡茶, Six Hills Tea) is produced nowadays by more than 30 counties of Guangxi Autonomous Region (广西) in the basins of the rivers Xun Jiang 浔 江, Yu Jiang 郁江, He Jiang 贺 江, Liu Jiang 柳江 and Hong he 红河. Its story has started at the Ming Dynasty in the Six Hills area (Liu Bao, 六堡, is literally translated as Six Fortresses) of Wu zhou district (梧州) in the eastern part of Guangxi, in the Xi Jiang (西江) River Basin.

(photo: Liubao area)

It is usually made of shoots with two, three and four leaves. The first stage of production takes 20-30 days and involves initial drying, steaming, twisting, stacking and final drying. The resulting tea leaf is ready to be consumed, which is exactly what the local farmers do. But the main bulk of the prepared "mao cha" is pressed and laid down for ripening. The first year tea resides on low shelves in a cool dark place. Then it is transferred to a ventilated area where it will be stored for at least another year. The last storage is dry, here it will gain in strength for more several years. After such a long maturation (from 3 to 10 years), the high graded Liu Bao is finally considered ready. Local residents believe that such aged tea is very good for health, and use it to prevent colds and as a medicine.

(photo: Liubao Heicha in tiles, rolls and loose sheets, prepared for shipment to Russia for "Moychay.ru" company)

In brewing Liu Bao tea gives you a feeling of rustic comfort, with its haylofts and chicken coops, persistent aroma of the steppe herbs, rotten wood, frankincense and milk.

(photo: CEO "Moychay.ru" Sergey Shevelev and tea technologist at the Liu Bao farm)

HEI CHA FROM HUBEI PROVINCE

Lao Quing Cha (老青茶, Old black tea) or Hubei Cha (湖北茶) is being made in Xianning district Hubei province (咸宁市湖北省) for at least 400 years. Having a large number of rivers and lakes (just over 1300), Hubei is called "the province of a thousand lakes". The hilly areas in the southwest of the current Xianning District were famous for its tea since ancient times: the tea culture came to this area in the seventh century.

(photo: Xianning district Hubei province)

According to the historical records, in the times of Ming Dynasty, the brick tea which were made here were sent down the Gan river, and then the Yangtze river through Hankou to Henan, via Shanxi to Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang. Since the eighteenth century tea caravans also transported tea from Hubei Province to Russia.

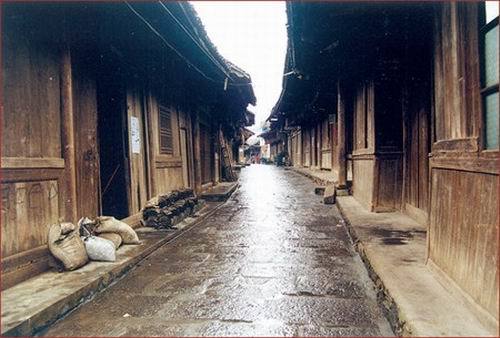

(photo: Yang Lou dong street)

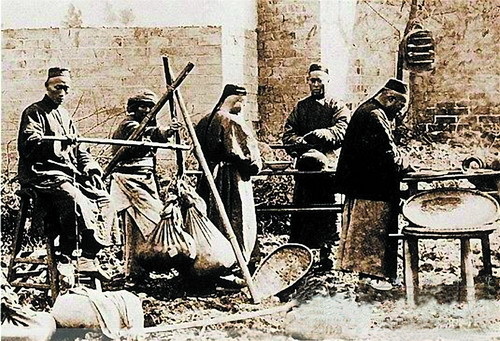

In the nineteenth century Russian tea merchants, who called Tea Kings established their trade offices and factories in Yang Lou dong (羊楼洞), a small town located on the territory of the present Xianning County.

(photo: tea packaging, family production, Yang Lou Dong, XIX century)

The tea craft here is passed from one generation to another. Lao Qing Zhuan Cha (老青砖茶, Old black brick tea) is traditionally made of two types of raw material. The inner layer passes through four processing stages: initial drying, twisting, stacking and final sun-drying. The external layer passes through seven stages: initial drying, first twisting, first drying in the sun, frying, second twisting, stacking and the final sun-drying. It is divided into three grades according to the colour of the tea cuttings, which indicate the age of the material. If the cuttings are green it is the first grade, red with some green on top is the second, and if they are completely red then it is the third grade.

(photo: Laoqing zhuan cha)

HEI CHA FROM SICHUAN PROVINCE

Sichuan Province is one of the oldest tea regions of China. Its geographical proximity to Tibet (called Zhang here) has contributed to the exchange of goods between the local people from the most ancient times. The harsh high-altitude climate and meager rocky soil make it impossible to cultivate most of the crops on Tibetan plateau, which is why the diet of its inhabitants is dominated by meat, fat, and carbohydrates. Tea on the other hand helps to absorb heavy food and compensates the deficit of vital vitamins and minerals.

(photo: Tibet)

The Tibetan drink is called cha-suyma (whipped tea), or Bo-cha ("Bo" is the ancient name of Tibet). To cook it you need yak milk and butter. A pressed tea brick is boiled in yak milk for several hours until the liquid acquires a dark brown colour. Then it is whipped with melted butter and salt until it is homogeneous. A result of this is a high-calorie energy drink, which Tibetans honor as the most nutritious and healthy beverage in the whole world. It has a peculiar taste, quickly restores energy and relieves fatigue, which is extremely important when traveling on foot in the mountains. Until at least the XX century in Tibet the distance walked in the mountains was often expressed in bowls of tea. Three large bowls are approximately equal to eight kilometers. Instead of a dessert the tea is served with "tsampa", which is a meal made of over-fried grains of barley.

(photo: Tea in a Tibetan monastery)

Tea production, designed specifically for sale to Tibet began in seventh century. It was then that the tea was in there for the first time officially as a dowry of the Chinese princess Wencheng, became the wife of the Tibetan ruler Songtsän Gampo. Caravans laden with the tea and other essential goods started to go through the mountain passes and high peaks via a dangerous but delightfully beautiful road. Strictly speaking, this route was already known in the era of the Western Han Dynasty, when it was called Du Shu Shen Dao (The road between Sichuan and India). But in the ninth-tenth centuries, when the popularity of tea from the Northern gardens (Fujian province) started growing in the palace court (until that time, the court preferred the tea from Sichuan), it was more common for the Sichuan and Yunnan farmers to sent their tea to Tibet and Central Asia in exchange for horses and rare Tibetan medicine. Therefore, the road was named Cha Ma Gu Dao (茶马古道, Tea-horse-road). The special trade agency created in Sichuan in 1074 established the rate: one horse for 60 kilograms of pressed tea. Thus, by the beginning of the XIII century, about 25 thousand hardy Tibetan horses were sent to China every year.

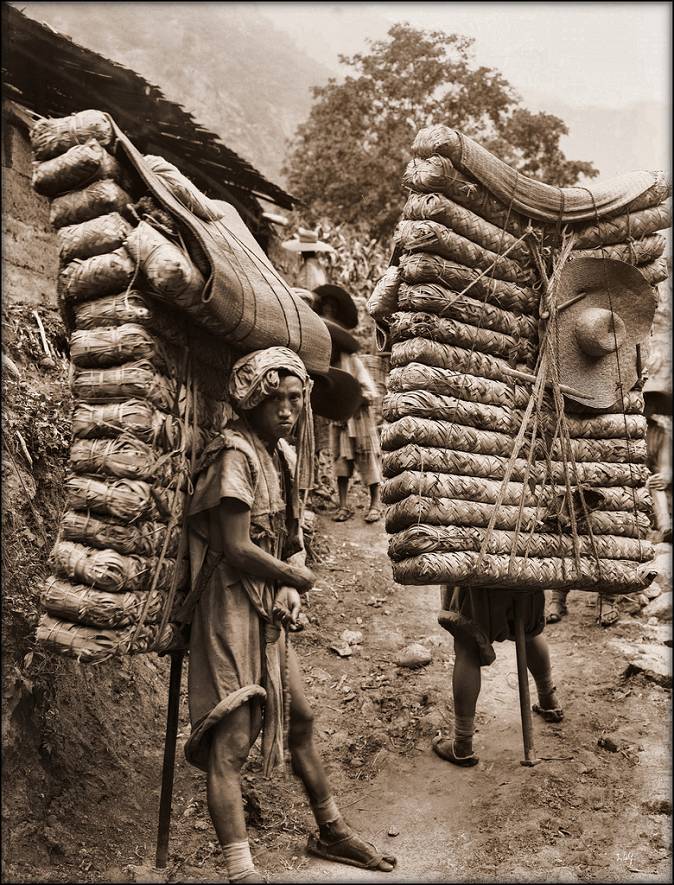

(photo: Tibetan horse)

Tea was picked up at tea plantations around Ya An (雅安) and delivered to Kangding, with carriers climbing 2550 meters along the way. The way from Ya An to Kangding took an average of 21 days. Tea was packed into 8-kilo bags. One porter was usually bearing 10-12 bags on his own. For men and women luggage weighing 70 to 90 kilograms was considered normal (a strong man could carry 135 kilograms). Excluding the valuable cargo, the carriers had to bear a pair of spare straw shoes and a dry ration. They could have travelled only 3-4 kilometers per day, taking a short rest every 50 meters. This way, getting to the destination required a whole month. In Kangding the tea was sewn into bundles made of waterproof yak skin. The final part of the way to Lhasa the cargo was carried on mules and Tibetan horses.

(photo: Tibet, mountain road)

Undemanding to the taste and aroma subtleties of the tea, consumers from Tibet and Central Asia have always appreciated its nutritious energy. Therefore, southern Sichuan tea is traditionally produced from rough leaves and fresh stems. Mao Zhuan Cha (毛庄茶) processing involves wilting, panning in a wokand the final drying. Zuo Zhuang Cha (做庄 茶) processing involves sun-drying alternated with wet stacking. Ready-to-drink tea is traditionally compressed into a brick shape or entwined with bamboo leaves for easy transportation and storage.

(photo: tea porter, XIX century)

There are several varieties of Tibetan tea, which differ by the quality of raw material (from the rough mature leaves with cuttings and fragments of stems to the gentle early buds with two leaves).

Nowadays Sichuan hey cha is divided into Western (produced in Guan Xian 灌县, Chong Qing 崇庆 and Da Yi 大邑), mainly used for domestic consumption, and Southern (produced in Ya An 雅安, Tian Quan 天全, and Rong Jing 荣经) which is exported to Tibet and Central Asia and is also called Bian Xiao Cha (边销茶 , Tea for sale in the border areas) or Zang Cha (藏茶, Tibetan tea).

In our store, you can always buy Chinese Heicha, handmade in small farms located in the historical places.