Georgian tea is a Northern product. Its history has been modelled by romantic dreams and energy of enthusiasts, talented entrepreneurs and hard working scientists, heroic efforts of usual workers and technical imagination of engineers. Through a long and difficult period of development, it came to a brilliant moment of flourishing which was immediately followed by degeneration and almost oblivion. However, wherever a tea bush was once planted by a hand of a man who cares - their common story surely has a continuation.

Photo: an old tea plantation in Kobuleti.

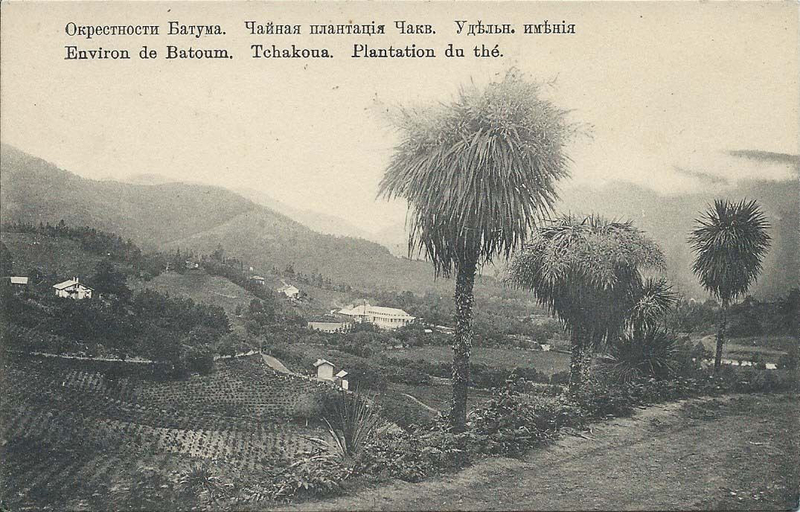

"... This happy corner of subtropical climate where every tea bush is growing just as well as it would in China - is located at the southernmost borderlands of Georgian part of the former Soviet Union - previously, Batumi district. It is here, in between evergreen azaleas and rhododendrons, where the displaced Chinese migrant - teabush - found a new home. He - who would like to spend a summer holiday in an exotic subtropical environment, to rest in wonderful gardens in the shade of Japanese palm-trees, Zelanian dragon-trees and Australian eucalypts - is strongly adviced to go to the new homeland of Soviet tea - Batumi Black Sea shore. Here he will see charming low slopes engirdled by stepped terraces of reddish soil with planted tea bushes.

Tea bushes of low size - not above 1 arshin (28 inches) from the ground - are kept in perfect condition and gladden the eye of a tealover with their evergreen leaves. After a short period of winter standstill (the warm Batumian winter only lasts for a few weeks, and the temperature never drops below 7,5 C), the teabushes start to grow again in March, and develop new leaves during all summer and then, all autumn which is amazingly clear and warm here as well..."

K.K. Serebryakov "History of Russian tea", an article in "Herald of Knowledge", 1927.

In XIX century tea became a very popular drink in Russia. It was imported by tens of thousands of tons (both legally and illegally), also ait was faked and doctored. Expensive grades were sold by 10 - 12 roubles per lb, which was an equivalent of the price of 2 or 3 cows. This tremendous popularity made people think about opportunities to cultivate tea inside the country. The Caucasian coast was the best place for doing this in terms of climate. (Georgia was a part of the Russian Empire from 1801 to 1917). Before some practical steps in this direction were made, there had been more than 30 scientific and popular researches published on this subject.

First tea bushes together with some other exotic species were planted in Russia immediately after the wars with Napoleon. Armand-Emmanuel du Plessis, Duc de Richelieu, Governor of Herson, ordered to bring first plants in then recently set up Imperial Government Botanical Garden (now Nikitskiy Garden) in Crimea next to Yalta, in 1817. The first experiment failed, all the transplanted bushes died. In 1833, the new General-Governor Prince Michael Vorontsov made an order to bring a new batch of shoots from China. That time, the plants survived and brought seeds. The director of the Garden Nikolay Gartvis thoroughly studied conditions appropriate for their wellbeing, and recommended to move further experiments to the Caucasian coastlands of the Black Sea. In 1848, the tea shoots were sent from Nikitskiy Botanical Garden to Sukhumi and Ozurgeti.

The first 200 bushes delivered to Ozurgeti were planted in the State-owned garden, previously owned by Gurieli princes. During the military campaign of the 50-s, the Turks brought the garden to ruin, and there were only 25 of them left. The other batch was sent to Mingrel prince David Dadiani, replanted in his gardens and successfully cultivated. As a rare exotic plant, the tea bush attracted a lot of attention from botanical lovers and was very popular in the private gardens of Guria and Mingrelia, Sukhumi and Sochi, as well as other places all around. When properly attended, tea bushes could grow, blossom and bring seeds. But, there is a significant difference between growing a few tea bushes in one's private estate and winning an official budget from the government to organize a big scale production.

The first 200 bushes delivered to Ozurgeti were planted in the State-owned garden, previously owned by Gurieli princes. During the military campaign of the 50-s, the Turks brought the garden to ruin, and there were only 25 of them left. The other batch was sent to Mingrel prince David Dadiani, replanted in his gardens and successfully cultivated. As a rare exotic plant, the tea bush attracted a lot of attention from botanical lovers and was very popular in the private gardens of Guria and Mingrelia, Sukhumi and Sochi, as well as other places all around. When properly attended, tea bushes could grow, blossom and bring seeds. But, there is a significant difference between growing a few tea bushes in one's private estate and winning an official budget from the government to organize a big scale production.

Prince Michael Eristavi played a great role in the history of Georgian tea. He was the first person who not only had grown his own tea, but processed it according to the necessary rules, and sent to an exhibition where it got recognition. Prince Micha Eristavi had no education in agriculture, nevertheless he was growing tobacco, cotton, citrus and other subtropical plants at his farm in Guria. He developed a plan of a complex subtropical estate with tea and wine production, growing fruits and silkworms, according to which the teabushes were planted in the part of the garden meant to serve as a wind break belt.

Unfortunately, this enthusiastic tea farmer didn't find support on the government level - his request for a credit to expand the tea plantations wasn't granted. After his death, the agricultural estate was inherited by his son A.Eristavi, who later moved to Sankt-Petersburg, and gradually deteriorated.

Attempts to unite efforts of some individual enthusiasts failed as well. In 1872, the editor of newspaper "Caucasia" E.Stalinskiy organized a group of investors who wanted to make a partnership and issue shares for the future tea business. A famous specialist in tea culture captain Valter Layel had been invited from Kalcutta with all necessary seeds and shoots, and he'd already given promises of guaranteed success. But the request for free land to develop the production was not satisfied by the authorities, and the group dissociated.

Many famous Russian scientists supported the idea of growing tea in Caucasia, including members of the Academy of Sciences Butlerov, Mendeleyev, Wiliams and Zeidlits.

In 1884, Magister Zeidlits presented his article on "Growing tea tree behind Caucasia" at the International Congress of Botanics and Horticulture in StPetersburg. Furthermore, beyond this theoretical research, he undertook some practical steps to perform the idea, with the intention to continue his experiments in his private estate near Batumi. Zeidlits addressed the Director of Russian Society of Shipping and Trady - admiral Chikhachyov - with a request to bring tea seeds and shoots from Hankow. Unfortunately, all the precious cargo was desinfected by caustic lime at Batumi customs in July of 1885. In despair, Zeidlits gave what was left of the materials to a retired engineer-colonel A.Solovtsov who later continued the business. Some of the shoots survived. Well cared for, they started to bring seeds. Solovtsov's tea won the big golden medal at the agricultural exhibition in Tbilisi in 1893. Then after his death, the plantation degenerated, but was reanimated during the Soviet period.

Only by the end of XIX century the whole of accumulated experience became big enough to launch the first serious experiment with commercial tea production in Caucasia. Company "K.and S.Popovy" purchased about 300 hectars of land in Salibauri, Kapreshumi and Chakve areas to set up tea plantations in 1892. A hereditary merchant Konstantin Semenovich Popov had years of experience in tea trade, and owned several tea factories in China in Hankow. In 1889, 1891 and 1893, Popov travelled to tea plantations in China, Japan and India, in order to thoroughly study all aspects of tea business – from growing seeds and seedlings to technologies of processing tea leaves. Another passionate advocate of the Georgian tea idea, an outstanding pharmacologist and expert on medicinal plants, Professor of Moscow University Vladimir Andreyevich Tikhomirov was also a member of the expedition of 1893. A large collection of tea seeds and cuttings collected in various tea producing areas has been planted in the gardens of company "K. and S. Popov". In total, company "K. and S. Popov" invested over a million rubles in this business.

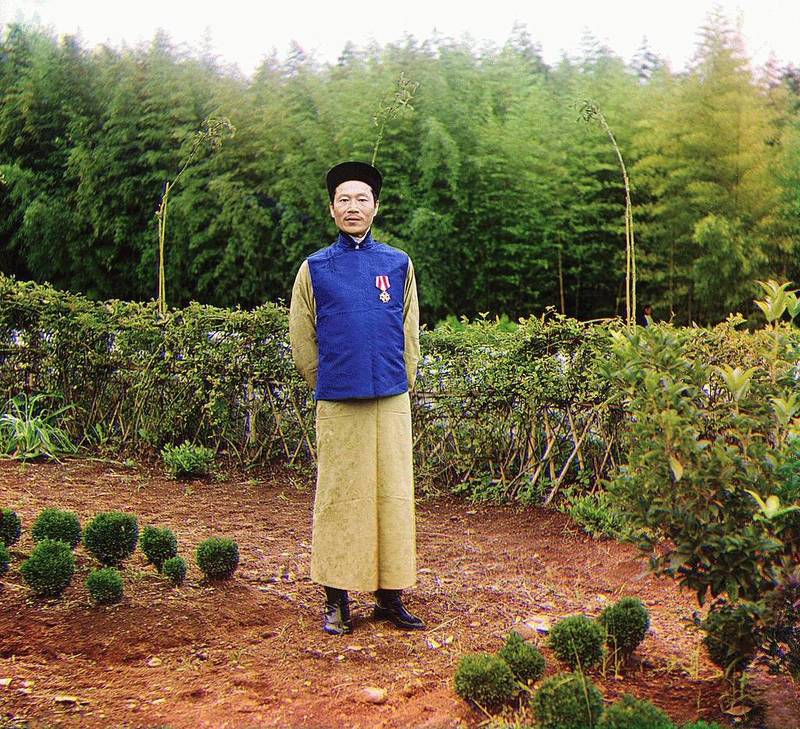

For supervision, K. Popov invited a Chinese specialist - a former assistant to the Director of a tea factory in Ninjo. Although in the history of Russian tea he became famous under name Lau John Jaú (rules of transcription of Chinese words into Russian were little known at that time), his real name was Liu Jun Zhou (刘峻周). Liu was born to a Guangdong Hakka family at Hunan province in 1864. As was noted in the "cadastral birth registry, his family tree goes back to Lu Ban, the founder of the Han dynasty, to whom he was 76th descendant. At birth the boy was given name Liu Zhao Peng (刘兆彭). Fifteen years of age, Liu went to Zhejiang province to study tea. In 1888, he met K. Popov in the town of Ningbo, and created a very good impression. Later in 1893, when Liu was already an assistant manager of a tea factory, Konstantin Semenovich asked him to become the head of their tea department in Chakva. "...I was attracted to a completely new country for me and the knowledge that I'd be the first one to introduce tea culture – Lau recalled later. – Having finally decided to go I signed a contract with C. S. Popov for three years. My allowance amounted to 500 rubles per month with an apartment, food cost, servants, horse and carriage and so on. Even travel there and back in the first class was included. I arrived to Caucasus in November 1893." Together with Lau, there arrived ten assistants - Chinese specialists - and ten thousand cuttings of tea bushes and several hundred pounds of seeds.

Tea produced under Lau's supervision was presented at the Paris exhibition and received a gold medal.

In 1897, the company ordered equipment for a large mechanical factory (driven by an oil engine) similar to the Ceylon model, from England. Processing volume of the factory was 200 tons of raw tea leaves per season at the time. In 1898, the factory made 13 thousand lbs (5200 kg) of ready tea.

Photo: after 10 years of excellent service, Lau was awarded by an order of St. Stanislaus, bought a small piece of land near Batumi and built a house there. WIth the Emperor's permission, he produced tea under a label of his own.

The path taken by K. S. Popov was followed by the Department of Specific affairs (the Russian State institution that was managing the Imperial family property from 1797 to 1917). In 1895, it started purchasing quite extensive lands in Chakva, and organized an expedition to South-East Asia, led by some best scientists of the time — agronomist and expert on subtropical crops I. N. Klingen, an ardent patriot of Southern Colchis, the future founder of the Batumi Botanical garden, Professor A. N. Krasnov, and agronomist V. Simonson, who after having returned from the journey wrote "The practical guide to cultivation of teabush".

In 1896, the expedition returned with six thousand tea cuttings and two tons of seeds. But while it was still travelling, the Imperial estate in Chakva entered a contract with A. Solovtsov, and 20 arpents of the land were already sown with material from his plantations. By 1900, the Imperial Estate owned 98,5 hectares of tea plantations, and by 1917 - about 550 hectares. The cultivated grades were mostly Chinese, however there were also Indian and Japanese plants. Indian grades could not survive the climate conditions, and Japanese plants were later replaced by varieties with larger leaves. Some farmer grades from Yanloudun and Ninjo, as well as Indian-Chinese hybrid Kangra imported from Western Himalayas, were recognized as the best material for cultivation.

In 1899, a tea factory was built, with processing capacity up to 1 million kilograms of raw leaves. The first 930 lbs (370 kg) of tea was then produced. In 1901, Lau John Jaú left his position at K. Popov's and started working as the Director of Chakva tea factory (he was working there for the next 25 years, was awarded with the Order of the Red Banner of Labour by the Soviet government in 1923, and finally returned to China in 1926). A significant part of the Georgian plantations was later sown with seeds from Chakva. It was here at the factory where the first Georgian tea masters were trained.

Local residents working at plantations of Salibauri and Chakva estates got experienced in tea cultivation and applied their knowledge in their villages. In 1910, the total area of tea plantations in Adjara grew up to 125 hectares, and the number of tea farms increased to 101. However, small entrepreneurs preferred to sell raw leaves to Chakva factory rather than to cope with various necessary formalities themselves. The excise system demanded that weighing and packing was performed in the presence of an official in special rooms. Another requirement was that labels had to be ordered from a printery, all the hustle about sales still being the task of the producer.

Despite the success of tea initiatives of Prince M. Eristavi, commercial cultivation of tea culture in Western Georgia – in Ozurgeti, Senak and Zugdidi districts - began a little later than in Adjara. Here, it was mostly maintained by small tea farms. The only tea factory was located in the princes Nakashidze estate in Guria. The factory was built in 1908. It was equipped with a 25 horsepower electric motor, a roller and a brick oven with a chamber made from metal sheets. Its yearly processing capacity was up to 8000 kg of raw leaves.

A big contribution to developing tea business in Guria was made by Prince Ermile Nakashidze. Being an educated agronomist, he travelled a lot in Guria, Mingrelia, and other areas in search of better lands for setting up tea plantations. He taught local peasants artisanal ways of processing tea leaves, and then he became the initiator and the supervisor of a tea factory construction in Ozurgeti, with Anaseuli and Nasakirali branches. He translated a booklet on tea by agronomist S. Timofeev ("The brief instruction on cultivation of tea bushes in the Western part of Kutaisi province") into Georgian language, and distributed it to the poor neighborhood. His enthusiasm resonated in the hearts of ordinary people, and many became engaged in tea-planting, growing tea and selling raw leaves to the factory.

After the establishment of the Soviet regime, Prince E. Nakashidze became one of the initiators of joint stock company "Tea-Georgia". He actively participated in establishing tea farms in Chakva, Salibauri and Zedobani. In 1928, he published his book "Tea bush, its cultivation and tea processing".

photo: harvesting tea in the Imperial estate, around 1907-1915. A digital color image from negatives of Prokudin-Gorsky

In Abkhazia, where the first Georgian tea bushes were initially planted in 1848, there were no large industrial plantations or factories before the Russian revolution.

In 1885, academician A. M. Butlerov set up a small tea plantation on a piece of land of his own between Sukhumi and New Athon, and even produced his own tea. Since 1900, the Russian Ministry of Agriculture under guidance of Professor S. N. Timofeev has organized a few small pilot plantations in Abkhazia. The first big tea farm in Abkhazia was set up by farmer Razhden Todua. Having spent several seasons in Chakva, he finally decided to make a business of his own. In the spring of 1914, he planted seeds from Chakva on his piece of land of 0,5 hectares in village Pokveshi in Ochamchira district, and in 1917 he picked his first harvest. He sold his hand-made tea under brand name "Todua" at Ochamchira market.

In total, three large tea factories equipped with English machinery and a few smaller handicraft farms were working in pre-revolutionary Georgia. They processed raw leaves harvested in their own farms as well as purchased from owners of small plantations. By keeping prices for raw leaves pretty high, the owners of the factories stimulated further development of tea-cultivation. Totally, there were about 1,000 hectares of tea plantations in the area by 1917, and the total volume was 140 tons. Despite the fact that the volume of tea imports to Russia was 75800 tons that very year, the share of Georgian tea in that number was less than 1%. Nevertheless, a good beginning is half battle.

Tea grades produced before the Russian revolution - "Bogatyr", "Kara-Dere", "Zedobani", "Ozurgeti" - were of rather high quality. The best reputation was enjoyed by the tea factory of K. S. Popov. Popov's tea received high marks and awards at Russian and foreign exhibitions. However, most of the produce was low-grade "soldier's tea" made at the Imperial estate factory and sold to the Military Department "for supplying lower army ranks".

photo: company "Brothers K. and S. Popov" had the copyright to put the image of the state emblem on the package, advertising and labels since 1894, and it was granted the title of "Supplier of His Imperial Majesty" in 1898. It was also the supplier of several European Royal and Imperial courts: in Greece, Belgium, Romania, Sweden, Italy, Austria and for the Shah of Persia.

The first World War stopped the development of tea-growing in Caucasia: many tea areas happened to be in the front line. In April 1918, they were occupied by the Turks, then the Turks was replaced by British troops. Tea farming has come to full desolation. An acute shortage of bread forced peasants to forget about tea, and sometimes even destroy tea bushes, sowing corn instead.

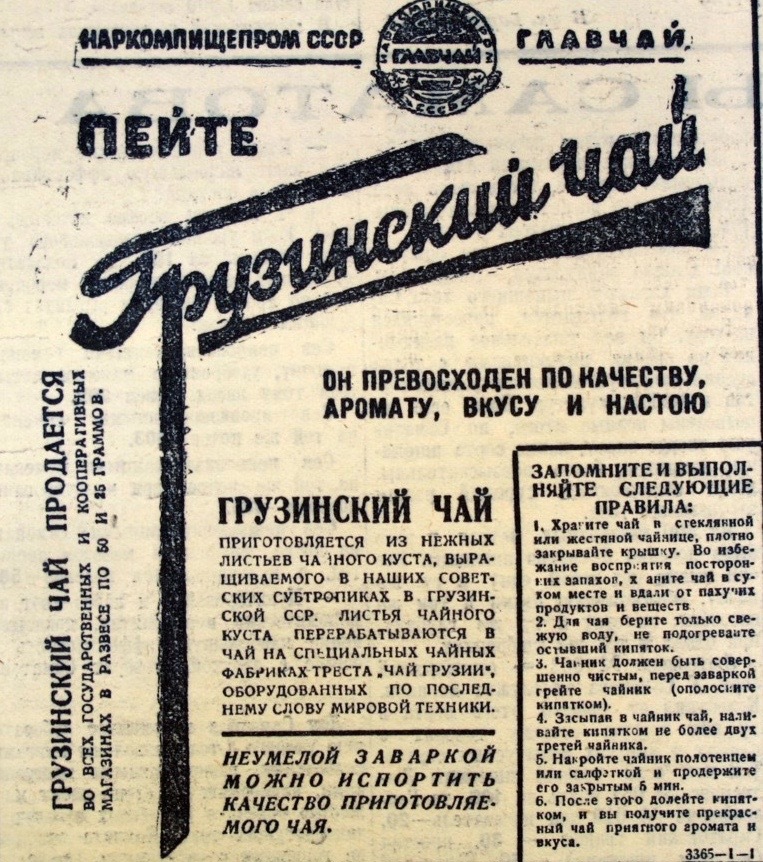

After the October revolution, the property of both large and small tea companies was nationalized. Distribution from confiscated warehouses was delegated to Soviet organization "Centrochai". In July 1921, the first ever Congress of tea growers of Adjara was held in Chakva. Some measures were developed, to revive the tea industry in the region. Soon an unprecedented (in the whole history of CHakva factory) daily harvest was collected and processed. In July 1925, 80000 kg of tea (10 wagon loads) was sent to Nizhny Novgorod Exhibition.

In the end of 1925, State joint stock company "Tea-Georgia" (originally called "Tea-Colchis")became the head of tea cultivation in the area. Development of tea industry in Caucasia was regarded by the government as a program of great significance: tens of millions of rubles were spent annually on developing tea plantations. Farms could use those budgets on an interest-free or concessional basis. Tea-growers were also supplied with bread at a low price. And as soon as introducing tea was accompanied by expulsing corn, tea growers were also supplied with grain in accordance with the size of the land.

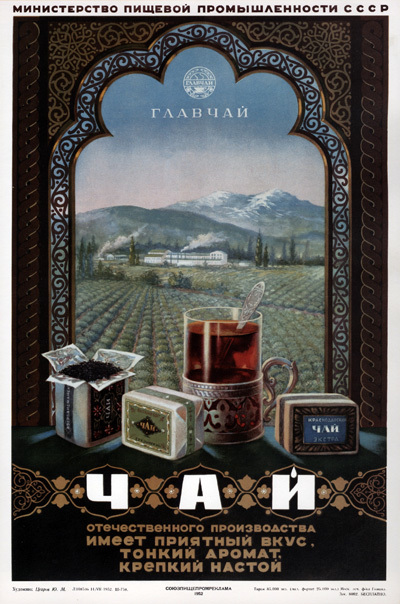

photo: Georgian tea advertisement, 1930-s

In the summer of 1926, joint-stock company "Tea-Georgia" opened an experimental station in Chakva, and in 1930, All-Soviet Union Scientific Research Institute of Tea Industry was established. The Institute included Zvanskaya, Chakvinskaya and Zugdidskaya experimental stations, and later its branch offices in Sukhumi and Poti were opened.

Introducing a new little known culture was a challenge and demanded a lot of enthusiasm from workers. Lack of theoretical knowledge and practical experience forced to contact the experts from abroad and learn from their mistakes. For example, the trench planting method proved to be unsuitable for our conditions. Wrong as well was the recommendation to plant seeds of Indian grades not adapted to our climate.

For setting up the first Georgian plantations, 492 tons of seeds were purchased from India, 390 tons - from Japan, and 39 tons - from China. To purchase the seeds gold was needed, so one of the tasks of primary importance was to refocus on the local seed material. It was solved by 1932, after which Russia used only seeds grown at the local plantations.

In 1948, Xenia Ermolaevna Bakhtadze succeeded in developing unique hybrid grades "Georgian №1" and "Georgian No. 2". Their yield was 30-35% beyond ordinary. For this work she was awarded the Stalin prize. In total, during many long years of breeding experiments, K. E. Bakhtadze obtained 19 new varieties of tea adapted to our conditions. One of them - "Georgian No. 8", later named "Hero of Winter", - could endure 25-degree cold under the snow! Nowadays, this is the main tea culture in Dagomys in Krasnodar Region.1926 г.

photo: Hero of Socialist Labour, academician Ksenia Bakhtadze

To provide professional advice, foreign experts were invited to Georgia in 30-s. In his memo to the Director of "Tea-Georgia", English doctor G. Mann wrote: "As far as Achigvari is concerned, we believe that the place chosen for setting up a tea estate is extremely poor, and we don't understand how such a development has been authorized". Indian planter V. Barber added in his report: "I will not hesitate to condemn this place... the perspective is most hopeless".

"Not at all! - replied the Communists. – Your capitalist methods certainly do not allow to fully reveal the potential of the area, but we will show to the world, what miracles a Soviet tea-grower is capable of!" And they did: Achigvari farm harvested 2618 kg of tea leaves in average from each of the 730 hectares of its plantations in 1959, and Johedjiani farm - 4693 kg from 490 hectares."

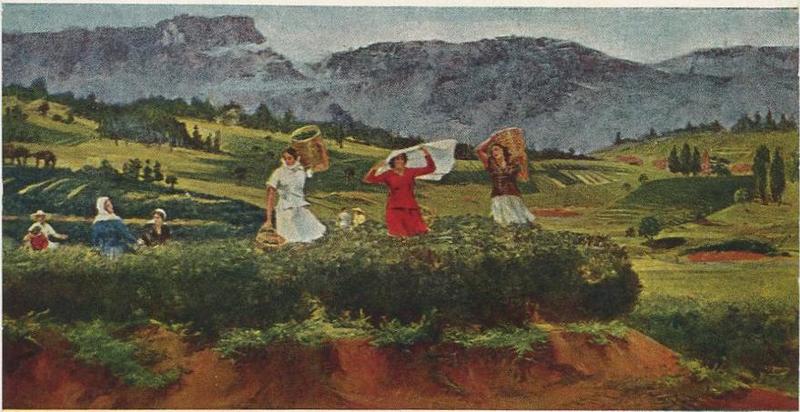

"Masters of high yields" started to appear - harvesting up to 40-60 kg of tea leaves per day on the average. Overachievers of the tea industry were extremely welcomed and encouraged. Field worker of Chakva collective farm Pazia Dolidze set a world record by collecting 120.7 kg of tea leaves in 1 day, on May 21, 1936. Yulia Pogorelova did 250% of the daily norm and harvested 3348 kg of tea leaves in 116 days at Ochhamuri collective farm. In 1957, a brigade led by Tatiana Chkhaidze harvested 8892 kg of leaves per hectare, in 1958 – 10015 kg, and in 1959 - 11090 kg per hectare on the average. Nina Gogodze collected 11 582 kg per hectare, and Tatiana Chkhaidze herself – 16 450 kg. Her dream - to surpass the world record of Ceylon tea-growers – came true!

Thousands of field workers picking tea leaves were awarded government awards, and some of them even became members of local authorities organs up to the Supreme Counsel of the USSR. That was an amazing way tea "led its inspired followers to the palaces" - while simultaneously manifesting a thesis of Lenin about "a scullery maid ruling the state".

photo: Hero of Socialist Labour Tatiana Chkhaidze (second from left) and her brigade

New tea factories were constructed "in full compliance with the latest achievements of science and technology", which were used in India, Ceylon and other colonial plantations. That was the era when ideas of progress, mechanization and mass product were entering our social consciousness. "Broad masses of peasants got involved in tea farming, replaced ancient methods of natural farming by modern ones", - proudly reported the newspapers of that time.

illustrations: L. P. Beria at tea plantations of Georgia. Painter A. K. Kutateladze

In 1921, Georgia produced 550 tons of graded tea leaves, in 1940 - 51300, in 1976 - 356 thousand tons. The average yield being 541 kg from 1 ha in 1921, in 1940 it reached 2292 kg, and in 1976 — 6800 kg. To compare with India (Sri Lanka) - where the vegetation season lasts for 11 (10) months - the average annual yield of Indian and Lankan plantations was almost the same as Georgian.

Since 1932, a new introduction had been made in tea processing - artificial withering of harvested leaves in special chambers constructed by Sh. Mardeleyshvili. This innovation allowed to reduce thrice the duration of the process which before was carried out under the sun on cement pads, and then continued on the shelves inside for 18-24 hours. Now withering took only 4-6 hours. Other innovations were introduced in the processes of fermentation, grading and drying.

When "Tea-Georgia" started working, the necessary factory equipment – rollers, ovens, graders and other machines - were imported from abroad. But from 1930-s all the machinery was produced at factories of Georgia, and was exported further on to all tea growing regions of the Soviet Union, as well as to Vietnam, China and Indonesia.

Since 1930, tractors were used for setting up new tea plantations, which allowed to bring considerable areas of virgin land (etseri) under cultivation. The Western swampy part of Colchian lowland in Georgia was a sinister place. Farmers did not have the strength to win even a piece of land under crops from the swamps, on top of that, malaria claimed hundreds of lives. Draining and development of wetlands required huge efforts and money. For that, as a result, swamps which previously covered\ the area gave place to tea and citrus plantations. Malaria has retreated along with swamps. Dozens of comfortable settlements grew at the virgin lands of Colchis.

Illustration: harvesting tea. 1957. Painter A. K. Kutateladze

One of the most time-consuming operations in tea-farming is selective leaf harvesting. Therefore throughout the twentieth century attempts were made to make it a mechanical operation. In 1910, Japan began to apply special hand scissors with blades 20 centimeters long, on one of which a bag to collect harvested leaves was fixed. However neither this Japanese tool nor any other facilities did not give a fundamental solution to the problem. The announced prize of 100 thousand dollars which was waiting for the inventor of a tea-harvesting machine in one of the European banks remained unclaimed. The invented in the 50-s British machine "Taripen" sheared everything indiscriminately and was not suited for cutting young flushes.

The Soviet Union started to work on mechanization of selective harvesting of tea flushes in 1928-1930 years, when trust "Tea— Georgia" held a competition for creating a tea harvesting machine. The trust was headed by Professor V. A. Zheligovskiy at the time. It began to receive proposals from innovators, inventors and scientists from all around the country. In 1933-34, machines "GIL-2" and "Lida" were tested, the latter turned out to be effective in harvesting "lao-cha" and easier pruning the ties. Another machine using the principle of easy breaking off tender shoots was tested in 1935. Further work on designing tea harvesting machines was conducted in the State Special Design Bureau for Agriculture of Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. Two years later, engineers of the Bureau proposed a cart machine of a comb-pneumatic type: the cart was equipped with a fan, a harvesting facility and an engine. That machine could harvest up to 60 % of the tea shoots. Finally, the dream of many generations of tea-growers came true with invention of "Sakartvelo" in 1963. "Sakartvelo" was the world's first tea harvesting machine of selective action which was designed to work on flat plains and moderate (up to 8 degrees) slopes. It was first tested at plantations of Ingiri tea farm in the north of Colkhis lowland.

"Sakartvelo" machine was moving along the tea ties at a speed of 1 km per hour. The working parts equipped with an automatically controlled hydraulic servo system, immersed into crowns of tea bushes with a height of 0.6—0.8 m. to the required depth. A curved comb with two rows of slanting rubber fingers with elastic inserts of reciprocating knives could sensitively probe shoots, select the flushes and find the most vulnerable spot to break (breaking point). The rough shoots were left just a bit crushed, but not torn. The other shoots - bended between the rigid supporting stationary blades and the working edges of the elastic inserts - broke. The strongly developed shoots with their fragile parts outside the range of the machine, were cut by the cutting knives. Flushes broken by the air flow from the fan, were pushed via the airduct and the flexible hose to the net conveyors, and then fell into the boxes of receiving bunkers. Since the machine was only harvesting standard leaves in good condition, an additional sorting procedure was no longer required. The bunkers accumulated up to 90 % of all mature flushes. The machine could process 0,2 ha per hour, saving labour of 25-30 plantation workers.

In the same year, "Sakartvelo" machines came into mass production at Tbilisi plant of agricultural machinery "Gruzselmash". For the originality and novelty, "Sakartvelo" was awarded a gold medal at the international exhibition "Modern agricultural machines and equipment" in 1966. Japan, USA, Kenya, Turkey and Ceylon made orders for it.

Next year, the All-Union Scientific Research Institute of machinery for tea farming and mountain agriculture developed a mechanically propelled machine CHA-650/900 that was able to work on steep slopes (up to 20 degrees).

photo: "Sakartvelo" at work

During the war there was a decline in tea production - it hit the bottom of approximately 14000 tons in 1942. Nevertheless, according to the rates of army supplies which were approved in September 1941, a soldier in the front line was supposed to get 1 g of tea per day.

Taking into account that the Soviet Union had a bigger need for green tea for the peoples in Central Asia at the time, Chakva factory was redesigned to produce bricks of green tea. By 1959, out of total number of 65 tea factories 8 were making only green tea.

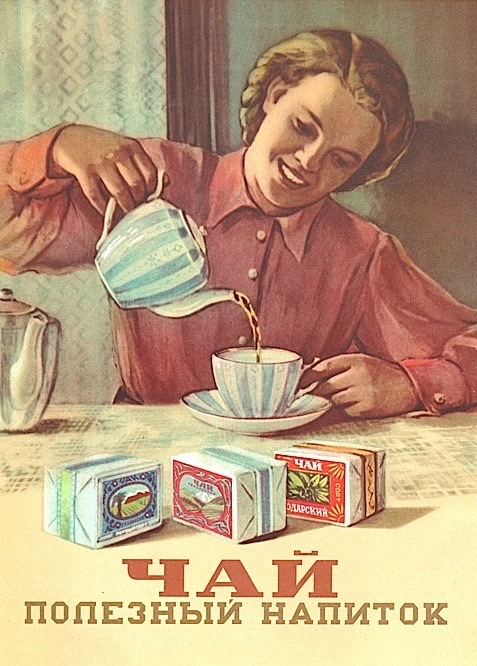

illustration: advertisement of tea, 60 years

Back in 1959, company "Tea-Georgia" produced 28142 tons of black pecoe tea, 5921 tons of green pecoe tea, and 8731 tons of green teacakes ("tea bricks"). Ready products were sent to tea-packing factories in Moscow, Odessa, Samarkand, Irkutsk and other centers of the Soviet Union, where they were packed in conventional paper, artistically designed gift cardboards, metal boxes, or porcelain caddies.

Black pecoe (from Chinese "bai hao") grades "Bouquet" and "Extra" were made from the upper leaves of tea bushes and contained also shoot apices. Top grade was standard cut black tea leaf from the first harvest - this quality was already lower. Second grade tea was produced from shoots by machines and contained a lot of impurities. "Tea No. 36" and "Bodrost" ("euphrasia") were blends of Georgian, Indian or Ceylon tea.

The range of green teas was wider, and contained a few dozen varieties of trading marks under different "numbers" — from No. 10 to No. 125 (according to quality rules, i.e. the number 10 corresponded to the lowest quaity, and No. 125 – to the highest). Beyond this scale of numbers, there were premium grades of superb quality "Bouquet of Georgia" and "Extra". Inside the numbers scale respectively: top grades were No. 111, 125; 1-st class - No. 85, 95,100, 110; 2-nd grade— № 45, 55, 60, 65; 3-rd grade— № 10, 15, 20, 25, 35, 40. Grades "Bouquet", "Extra" and "Highest sort" were meeting all the world's best international standards for green tea.1959 г.

illustration: advertisement of tea, 1960-s

The heyday of Georgian tea-growing came in the 60-70-s of the XX century, with an almost immediate decline after that. The transition from hand-picking to mechanical, as well as gross violations of technology (harvesting in wet weather, quickening the process by "cutting corners" - i.e. eliminating additional stage of fermentation and obligatory stage of drying, etc. - in the mindless pursuit of quantitative indicators had led ultimately to the complete degradation of quality. In addition, farmers and local authorities openly resented the production of tea, preferring to grow citrus cultures which brought more profit. Over 80 years, tea production volume in the Republic decreased almost twice, and after the collapse of the Soviet Union the local tea industry was virtually abandoned.

Out of the 27 factories which were operating in the region, today only 3 are left, the others having been restructured for a different function, and the machinery dismantled for scrap. Dozens of hectares of tea land in the plains and mountain slopes are overgrown with weeds and ferns, and run wild without pruning. The local population does drink tea, but people obviously prefer imported grades, the share of Georgian tea at the domestic market being not more than 10%.

Today, tea business in Georgia is going through hard times. The old factory in Chakva continues to produce "Kalmyk" green tea for consumers in Central Asia. As for production of labour-intensive premium grades - same as a hundred years ago, they are produced by artisanal ways by people who feel passionate about tea culture, those few enthusiasts for whom tea is not abstract figures of bureaucratic reports, but their favorite thing giving meaning to their life. But with this approach, the result is certainly worth all the effort.

In the early summer of 2016, the head of our company Sergey Shevelyov made his second visit to the manufacture in Georgia, and we made a video about this expedition:

As a result of this journey our tea assortment was enriched with several varieties of "KalmykTea" produced by Georgia, as well as high-grade red (black) tea. Go to online section of our virtual store dedicated to Georgian tea.